Reading the Brands: How Livestock Inspectors Caught Cattle Thieves in the Arizona Territory

"Feel along the edges," Grady said, pointing to the mark on the red Polled Shorthorn heifer's left hip.

Deacon ran his fingers over the brand with the careful touch of a trained veterinarian. The scar tissue was raised and irregular, not the clean lines of a properly applied brand. The hair around the mark grew coarse and in different directions, telling its own story of deception.

"Hair growth's different here. And here," Deacon observed. "This was burned over another brand."

In that moment of discovery, Grady and Deacon, from my novel Blood Justice, were using detective skills that separated real livestock inspectors from ordinary lawmen. Reading brands wasn't just about recognizing symbols burned into hide. It was about understanding the criminal mind, spotting brand forgeries that could fool casual observers, and building legal cases that would hold up in territorial courts.

The Science of Brand Detection

A cattle brand was more than a mark of ownership in 1890s Arizona. It was a rancher's signature, his legal claim, and often his family legacy passed down through generations. For livestock inspectors like Tom Horn, who became "probably the most famous stock detective in the U.S.,"¹ reading brands was both art and science.

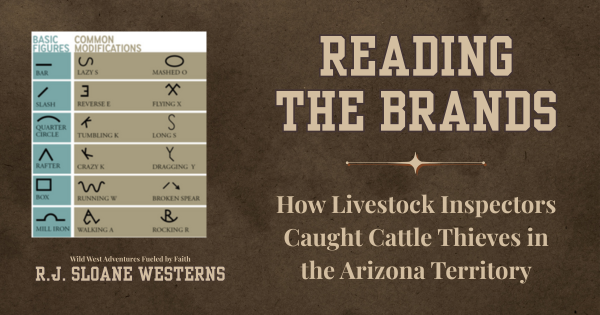

The basic rules were straightforward: brands are read from left to right, top to bottom, outside to inside, just like reading English. A "T Bar 9" brand would be read exactly as written. But criminals had their own vocabulary of deception.

When rustlers altered brands, they left telltale signs that trained inspectors could detect. The most obvious was scar tissue that didn't match the original burn pattern. Legitimate brands created clean, uniform scars that healed with consistent hair growth. Altered brands showed irregular healing, different hair textures, and raised scar tissue where new iron had been applied over old marks.

In Blood Justice, I show how Grady and Deacon discovered this systematic forgery: "T Bar 9" cattle had been converted to "I Bar 8" through careful iron work that would fool a casual buyer but couldn't stand up to professional inspection.

Pattern Recognition: A Detective's Best Tool

The most sophisticated livestock inspectors developed what we'd now call forensic techniques. When Deacon rearranged the brand sketches in the territorial office, he was demonstrating a crucial investigative method.

"When we're investigating brand theft, we need to compare similar marks quickly," Deacon explains. "A rustler who alters a 'T Bar 9' into something else is likely to pick another brand that starts with 'T' or uses similar elements."

This pattern recognition separated professional inspectors from casual observers. Instead of organizing brands by registration date, experienced investigators grouped them by similarity, allowing them to quickly spot which brands could be easily altered and identify forgeries.

Tom Horn used similar techniques during his legendary career. After learning tracking skills from Apaches during the Apache Wars, he applied that same attention to detail in reading cattle brands. His reputation for "doing whatever it took to bring down an adversary" made him revered throughout cattle country.

The Criminal Arts and Professional Detection

By the 1890s, cattle rustling had evolved far beyond desperate cowboys with running irons. The operations that livestock inspectors faced were sophisticated criminal enterprises with custom-made branding irons designed specifically for altering existing marks. These weren't crude modifications but precision tools crafted by skilled blacksmiths.

These operations included document forgery networks that produced bills of sale, shipping manifests, and health certificates using quality paper, proper government seals, and matching handwriting. Livestock inspectors had to become document examiners as well as cattle experts.

Grady and Deacon discover bills of sale signed by "B. Irving" from Flagstaff to Tucson, all with identical handwriting, paper stock, and ink. This wasn't some local rustler with a running iron. This was a coordinated network with connections to corrupt buyers, railroad officials, and even government bureaus.

The best livestock inspectors read more than brands and documents. They read criminal behavior patterns. Tom Horn's success came partly from understanding that rustling was often an inside job, requiring coordination between thieves, brand alterers, document forgers, and corrupt buyers.

Unlike frontier vigilantes, territorial livestock inspectors had to build legal cases that would survive court challenges. Deacon's methodical approach represents this new type of frontier lawman. He catalogs evidence and maintains detailed notes, while men like Tom Horn used photography to document altered brands, understanding that courtroom justice requires more than a strong suspicion and a fast draw.

Professional Tools and Lasting Legacy

By the 1890s, professional livestock inspectors carried more than guns and badges. They needed magnifying glasses for examining scar tissue patterns, measuring tools for checking brand dimensions, camera equipment when available, brand books for comparison, and legal forms for proper documentation. The job required veterinary knowledge, detective skills, legal understanding, and physical courage.

The techniques developed by Arizona's livestock inspectors influenced law enforcement across the American West. When Arizona achieved statehood in 1912, the professional standards established by those early inspectors remained, proving that frontier justice could be both effective and legal.

In Blood Justice, Grady Thatcher's journey from grief-driven revenge seeker to professional lawman represents this transformation. His partnership with the methodical Deacon shows how personal motivation could be channeled into professional excellence, how the desire for justice could be refined into effective law enforcement.

The next time you see a cattle brand, remember the men who learned to read them like detectives read evidence. In the dangerous Arizona Territory of the 1890s, the ability to spot an altered brand could mean the difference between justice and chaos, between legitimate ranching and organized crime.

¹ Monty McCord, Calling the Brands-Stock Detectives of the Wild West (2020)

Experience the dangerous world of brand detection and frontier justice in Blood Justice, where livestock inspectors use both scientific methods and personal courage to hunt down sophisticated criminal networks in territorial Arizona.